Chernobyl - thoughts and facts

Chernobyl used to be the name of a city in Ukraine on the border with Belarus - now it's a name of the most horrifying nuclear disaster the human race has ever known. It entered the lives of Ukrainian and Belarusian people on a peaceful sunny April day, right around Easter and before the May 1st yearly parade. Because the Soviet government wouldn't admit to the degree of the disaster and therefore wouldn't even broadcast that it happened until 2 days after the explosion (with a 20-second TV announcement), people didn't take a single prevention measure against radiation exposure to lessen the degree of impact. On the day after the explosion they were enjoying the bright sunshine and the gentle breeze, which apart from the lovely weather were bringing radioactive fallout.

Invisible, like the worst enemy, radiation sneeked into our countries on April 26th, 1986 with the explosion on a Chernobyl reactor, and imposing, like a lingering guest, wouldn't leave for many years to come (half-life of Plutonium is 24200 years). It deeply affected the lives of people in the area: abandoned homes, uprooted lives, unusable agricultural lands, contaminated rivers, lakes and forests. For years after the disaster people in many areas were not supposed to collect berries or mushrooms and would have to reduce the amount and variety of vegetables they grew in their plots of lands - a huge loss for nations whose daily ration consists to a high degree of self-grown vegetables or what they collect in the forest. But in many cases because radiation doesn't "hurt" and is not perceivable with any of the 5 senses, people didn't really follow those guidelines, which meant that the food consumed by people together with nutrients started to include radioactivite isotopes.

In deep shock and sympathy, the whole world turned to help. Sea air rich in iodine is supposed to help the body get rid of excessive radioactive elements, so many kids were sent to sanatoriums at the seaside of post-Soviet republics. I remember going one time to Azerbaizhan, then to the autonomous region of Kabardino-Balkariya in Russia. Japan was sending expensive equipment to Belarus to enable yearly thyroid tests for the whole population, but especially kids. And here's a curious twist in this account of the Chernobyl disaster: as tragic as it was and as shocking as it might sound, according to some intricate divine plan behind it, Chernobyl even resulted in positive changes in some lives, including mine. Within a few years after the disaster happened, many European countries introduced humanitarian programs to help prevent the Belarusian kids from developing chronical deseases associated with long-term exposure to high levels of radiation. The programs were about Belarusian kids spending some time a year (usually a month) away from Belarus - basically away from its air, water and locally grown food. That's how I went to England for the first time, and it's this event that I am sure defined the rest of my life - I learnt that the world is big but is just around the corner, accessible even for a Belarusian kid like me! There are many families like mine in Belarus these days: their kids have been abroad, being able to year after year practise a foreign language, get material help, learn another culture. But of course, this doesn't cancel out the fact that some families only suffered from the tragedy, as there's never a "common balance sheet" for any disaster...

Chernobyl tour:

"50000 people used to live here..." Apart from being an eery introduction to the "Call of Duty" game mission that takes place in the ghost town of Pripyat', it's also an accurate statistical fact. Pripyat' used to be a typical Soviet town in the Chernobyl area built for workers of the Chernobyl nuclear power plant, with Soviet blocks of flats, Soviet schools, kindergartens, restaurants, swimming pools etc. These days it's a deserted city in the 30-km exclusion zone around the Chernobyl plant, with crumbling blocks of flats, wildly growing plants and a haunted look and feel. For a Belarusian person Chernobyl is not really a tour place - it's a place where the disaster happened that directly touched our lives, so when Jordi and his mum went on a day trip to the exclusion zone, me and my mum didn't join them... Of course, I was very eager to learn what Jordi saw and heard, but it just didn't feel right to visit the location of the Chernobyl disaster in position of a tourist. Below I put together some information about this tour that I learnt from Jordi.

Chernobyl tour is arranged as a day trip from Kiev and includes visits to the area around the Chernobyl nuclear power plant and to the ghost town of Pripyat' in the 30 km exclusion zone. Anybody who wants to join a tour needs to contact one of the agencies in Kiev which are authorized to do these tours. This needs to be done 11 days in advance as the agency needs to apply for permits. During the tour brief stops are made at different places and people are allowed to take only the authorized pictures. Failure to comply with this requirement would bring about immediate termination of the tour by the guide. All throughout the tour the guide will show the current level of radiation by showing the screen of his bright yellow dosimeter. Just a couple of years ago the visit to Pripyat' used to include a visit to a school, but these days more and more buildings in the city are becoming increasingly hazardous due to years of desertation and are gradually being taken off the tour list. The tour's most striking part is probably the visit to Pripyat' town, but it's quite possible that it strikes more the foreign visitors who have never been to a Soviet city prior to their visit to Pripyat' (this is Jordi's opinion but I entirely agree with him). Kiev doesn't look Soviet, so for anybody joining this tour while on a trip to Kiev, Pripyat' can be really striking, as it means a typical Soviet town (which might be scary even without being deserted) plus the haunted look of the deteriorated buildings and wild vegetation. Since the tour is really expensive (about 150 dollar) and depending on the guide might fail to provide visitors with interesting and/or accurate information, I would suggest visiting a Soviet city (something like my hometown Osipovichi :-) and the Chernobyl museum in Kiev instead for an alternative - and almost free - package. The Chernobyl museum in Kiev is definitely worth a visit, as it's one of the few modern museums that manage to tell a story through silent artifacts.

Jordi's photos from the Chernobyl tour:

30-km exclusion zone, kindergarten:

30-km exclusion zone, view at the Novarka plant and reactor 4:

30-km exclusion zone, Pripyat':

Chernobyl story:

Back at school after Chernobyl happened, every year we would study things about radiation - types of isotopes, half-lives, methods of minimizing the exposure etc. During those classes we would discuss the Chernobyl disaster and its possible causes. But since at that time too little was known about the real causes, I don't remember getting a clear picture of what they were. The visit to the museum / Jordi's tour provided us with some information, and then I also did further research. Since the findings really struck me, I decided to put together in a concise form the story of Chernobyl (for me rather than for anybody else :-). During the research it struck me just how much numbers and facts vary across various websites, but since wikipedia articles on the subject looked very thorough and include references, I used it as my main source. Being Belarusian, I also relied on my own feeling about which conclusions and numbers look more reasonable based on the observable patterns of Chernobyl disaster affects in Belarus. The thing is, many of the websites that have articles about Chernobyl seem to be all too eager to sell a touching and horrifying story, and in the process sometimes overlook a simpler and maybe less dramatic truth. For more in-depth picture go to wikipedia (the guys who produced the articles on Chernobyl did an excellent job). And below is a short version of the Chernobyl story:

A summary of what led to the explosion:

The disaster happened during a system test on the reactor 4. The test was meant to actually patch an essential safety flaw in the design of the reactor. After the Chernobyl nuclear power plant had already been operating for a few years (!), it was established that in case of power grid failure, external power wouldn't be immediately available to run the coolant pumps that supply pressurized water to cool the reactor and the emergency diesel generators would start up only after about 1 minute delay. It was decided to try to bridge this one minute gap by using the residual momentum of the rotations of the reactor's turbine itself to generate the required electrical power for just one minute between the power failure and the full availability of the emergency generator. Three unsuccessful tests were conducted over the cause of a few years (1982, 84 and 85), and the one in 1986 was the 4th and last one.

The test was planned to be carried out during the scheduled shut-down of the reactor and according to the procedure (1) the thermal output of the reactor should have been no lower than 700MW and (2) the test should have been completed during the day shift. Here is what actually happened: the day shift started the test as scheduled and after a while the power output was down to 3200MW. That's when another regional power station accidentally (!) went offline and the Kiev electrical grid operator requested that further reduction of Chernobyl output should be postponed. Permission to resume tests came only at about 11pm - by this time the day shift had long gone, and the evening shift was preparing to leave, passing the test over to the night shift. Since they had limited time to run the test, the night shift carried out a rapid reduction of power output over the shift change-over. Such rapid reduction in thermal output resulted in even further drop due to the so-called reactor poisoning (a natural production of neutron absorber xenon-135). The power dropped below the minimum limit required for the test - to 500 MW. It was at this time that the young operator who'd only been working at Chernobyl for 3 months mistakenly inserted the control rods too far (!), which brought the reactor in unintended near-shutdown state and its thermal production - to about 30MW. And although shortly after that the control personnel of the reactor extracted the majority of the control rods to restore the power, the fact that for a while the reactor was operating at the power level of less than 200MW resulted in further reactor poisoning.

Various thermal-hydraulic alarms started going off at this time but were ignored to preserve the power. After a while more or less stable state of the power level of 200 MW was achieved so extra water pumps were activated according to the test scenario (as the turbines were supposed to run at full power). Since water absorbs neutrons (and the higher density of liquid water makes it a better absorber than steam), turning on additional pumps decreased the reactor power even further. This prompted the operators to remove the manual control rods even further to maintain the power. All these actions brought the reactor into what looked like a stabilized power level but in reality was an unstable state: the coolant reduced the boiling in the reactor but had limited margin to boiling - a state which would produce steam that had less neutron absorbtion capacity than water (and result in sudden power increase).

At 1:23am the experiment began: 4 out of 8 pumps were active, the steam to the turbines was shut off and a rund-down of the turbine generator began. The diesel generator started and picked up the loads. During this period the power for the 4 pumps was supplied - just like in the test scenario - by the turbine generator rotating down with the residual momentum. As this momentum was decreasing, so was the water flow rate - this resulted in increased formation of steam bubbles in the reactor core. These bubbles reduced the ability of liquid water to absord neutrons which meant increased power output (which in turn triggers more water turn to steam which would trigger increased power output and so on). This phenomenon of increased power output at low power levels was an essential design flaw of the Chernobyl reactors - it's called "positive void coefficient" and is listed first among the causes of the explosion.

At this time an emergency shut-down of the reactor was initiated with the mysterious pressing of the EPS-5 button (!) - the reactor emergency protection. The exact reasons why it was pressed are not known, but it brought about the automatic insertation of control rods into the reactor core. Now here's where the second major design flaw of the reactor kicked-in: the graphite-tip control rod initially displaced the water coolant before inserting the neutron absorbant, thus increasing the reaction rate at the lower part of the reactor core. So in a few seconds after the emergency shut-down was started a massive power spike occurred, the core overheated and the initial explosion happened. This explosion fractured the fuel rods, blocking the control rod columns, so they got stuck at about one-third of their possible depth (making it impossible to reduce power output at the maximum capacity of control rods).

The rest of those night's tragic events could not be read off instruments and was reconstructed with mathematical simulations. It's estimated that after the initial explosion obstructed the control rods, the power output continued to rise till it reached extremely high levels (of over 30GW). Steam from the destroyed channels entered the reactor's inner structure and tore off and lifted the 2000-ton upper plate to which the reactor was fastened, resulting in the first giant steam explosion, followed a couple of seconds later by another more powerful explosion which threw burning graphite blocks and fuel channels and the far more dangerous radioactive isotopes (such as caesium-137, iodine-131, strontium-90 and other radionuclides) into the air.

Because contrary to safety requirements a combustible material - bitumen - was used in the construction of the roof (!), fires started in the roof of the adjacent reactor 3. The local firemen arrived within 4 minutes of the explosion, the brigade from Pripyat' joined them after something like 10 minutes and more firemen arrived from Kiev after another 2 hours. The fires were extinguished by 5:00 (except reactor 4 where it continued to burn till May 10th) by the combined effort of those firemen brigades, helicopters that dropped over 5,000 metric tons of sand, lead, clay, and neutron absorbing boron onto the burning reactor and the injection of liquid nitrogen.

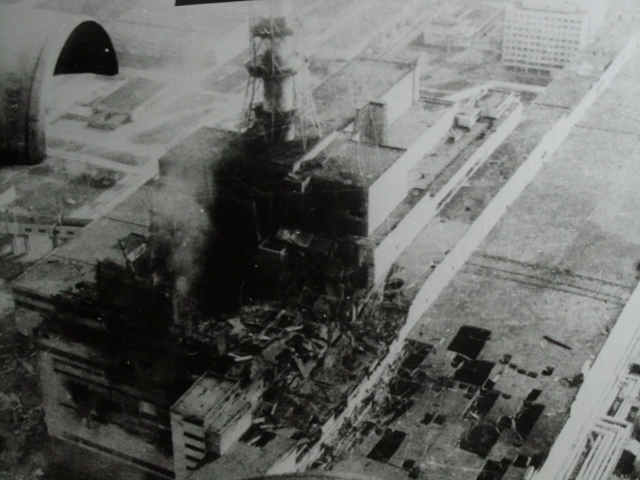

First photo of the Reactor 4 after the explosion, Chernobyl museum in Kiev:

Challenges of liguidating:

The biggest challenge about Chernobyl was that there was no experience of liquidating this kind of nuclear disasters. First the firemen needed to extinguish the fire: these men were not aware how dangerously radioactive the smoke was, they thought it was a regular electrical fire. Then the liquidators needed to collect the radioactive debris at the explosion site: there is a short video of instructions being given to the young men. They are being told that they would go into the most dangerous zone - of 10-20 Roentgen: they were smiling while listening to that, as they had no idea what it truly meant. In the same video you can see them burying the nuclear waste with just shovels. None of them had individual dosimeters capable of measuring such high levels of radiation (the usual dosimeters were continuously reading "Off limit"). They were working in the highly radioactive areas for just 1-2 minutes before being replaced by the next shift. But the truth is, at the time of the explosion the levels of radiation close to the core of the reactor were 10000 - 30000 Roentgen per hour, with a lethal dose of radiation being about 500 Roentgen over 5 hours, so many received the lethal dose immediately on arrival - 28 emergency workers died within a week from acute radiation syndrome.

Apart from (1) cleaning up the radioactive debris, liquidation activities included (2) draining the pool with "radioactive lava" that formed in the reactor core as pieces of fuel and graphite rods mixed with dirt and water; (3) collecting of nuclear fuel by a group of scientists to store it in a safe way and (4) building a cement and lead sarcophagus over the reactor. The sarcophagus was meant to prevent the possible self-sustaining nuclear reaction and was accomplished through an unspeakable feat of intensive construction work of a quarter million people over half a year.

Evacuation:

When Chernobyl happened, the Soviet government wouldn't admit to the degree of the disaster and would persist in conducting "business as usual", like the scheduled yearly May 1st celebration during which all the participants of the parade must have been exposed to levels of radiation much higher than they would've received had the goverment called it off. It was only when the workers of the Fomarsk nuclear power plant in Sweden found radioactive particles on their clothes and eliminated their facility as the source of radiation that the Soviet government had to admit to what had happened. The evacuation of Pripyat' was announed only 2 days after the explosion once the site was inspected by an official delegation from Moscow - by this time dozens of people in Pripyat' had fallen sick with radioactive desease. By May 1986, about a month later, all those living within a 30 km radius of the plant — about 116,000 people — had been relocated (this area is referred to as the zone of alienation).

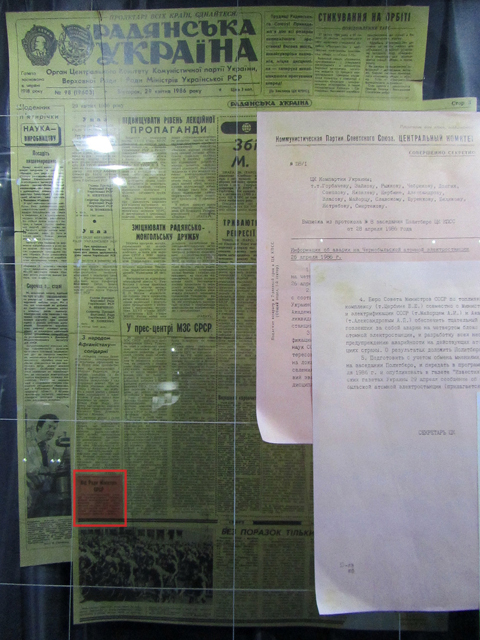

Check out the striking difference in the coverage the Chernobyl disaster got in a Ukrainian newspaper (3rd page, a few lines) and in New York Times (front page, big article):

Ukranian women during the May 1st parade and during the evacuation:

Radioactive fallout:

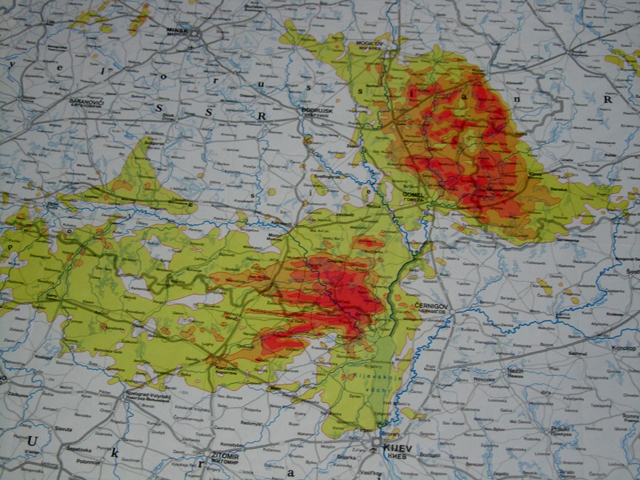

Although the cloud containing the radioactive fallout travelled all over Europe, most of the fallout settled over Belarus, north-western Ukraine and Bryansk region of Russia, with an estimated 60% of the total fallout ending up in Belarus. One of the reasons for such a high number for Belarus is that as the radioactive cloud was making its way from Chernobyl over Belarus, the Soviet government seeded the rain to prevent the cloud from reaching the major Soviet cities (I am guessing Moscow was their main concern). These days the disaster is costing Belarus 6% of its budget every year (with 22% in 1991).

Maps of the most contaminated areas based on the radioactive fallout (the darkest red are the Gomel region in Belarus and Chernobyl itself):

Decommissioning:

Chernobyl never stopped working in the strict sense of the word. After the explosion at reactor 4, the other three continued to operate because of the power shortage in the country. After a fire broke out on reactor 2 in 1991, the Ukrainian government finally decided to decommission it. Reactor 1 was shut down in 1996 and reactor 3 followed it in the year 2000. But carrying out all the stages of decommissioning will take years, so people are still working at Chernobyl plant removing the highly radioactive spent nuclear fuel, which is currently being placed in deep water cooling ponds on site and in the future will be placed in containers based on dry storage technology suitable for long-term storage. The workers at the functioning reactors don't have 9 to 5 kind of shifts: they work till the dosimeter shows that their exposure has reached the maximum permitted level for that day.

The remains of reactor 4 will remain radioactive for some time (as can be seen on a dosimeter screen during the Chernobyl tour). The isotope responsible for most of the external gamma radiation at the reactor is Caesium-137, which has a half-life of about 30 years. So it's possible that without any further decontamination work the level of the gamma radiation will be back to normal after about 300 years. It's the alpha emitters that have a much longer half-life, so the soil and other surfaces around the plant will remain contaminated with plutonium and americium for much longer. There is a plan to deconstruct the buildings as soon as it's radiologically safe to.

The new sarcophagus:

The original sarcophagus was built in a hurry and for at most 30 years. Since its maximum permitted lifecycle is about to expire, a new steel structure called the New Safe Confinement (NSC) is being built in its place to protect the reactor 4. Though delayed several times, construction finally began in 2010. It's financed by an international fund which is managed by the EBRD (European Bank for Reconstruction and Development). The NSC is being built by a French company Novarka (Jordi saw their plant right next to the reactor during the tour). They are building a giant arch-shaped steel structure which will slide down on rails over the current aging sarcophagus and the remnants of the reactor beneath it. Also about 95% of the fuel in the reactor at the time of the accident (about 180 metric tons) still remains inside the shelter, with a total radioactivity of nearly 18 million curies, so a separate deal has also been made with the American firm Holtec to build a storage facility within the exclusion zone for nuclear waste produced by Chernobyl.

Consequences:

Since there is still no precise methodology for measuring the effect of a nuclear disaster on humans, flora and fauna, the numbers and conclusions fluctuate significantly over various sources. According to wikipedia, these are some of the estimated numbers:

- 237 people suffered from acute radiation sickness (ARS), of whom 31 died within the first three months - most of these people were the firemen and the liquidators.

- Chernobyl explosion caused contamination of some major rivers, including the bio-accumulation of radioactivity in fish.

- 4 square km of pine forest around Chernobyl died after first turning red (hence the name "Red Forest") within a few weeks after the explosion.

- There were 4000 thyroid cancer cases registered by 2005. Most of them (about 95%) are treated successfully. Mostly children are diagnosed with thyroid cancer, probably due to high intake of radioactive Iodine-131 through milk during the first years after the explosion. Iodine is taken up by the thyroid gland to make hormones, so when the thyroid takes in the radioactive Iodine in place of the normal type, it causes cancer.

Mutations:

There has been an increase in mutations following the disaster, but not to the degree that would justify an image of the exclusion zone as a freak show where giant butterflies fly around huge plants with strange leaves and needles, and 4-legged 2-headed human-beings ride around on 8-legged 4-headed horses. Yet there has definitely been some increase in mutations: for instance, in the Chernobyl museum you can see an exhibit of a weird piglet with strange limbs, and a pine tree branch with unusual needles. According to wikipedia, on farms in Narodychi region of Ukraine, in the first four years of the disaster about 350 animals were born with major deformities such as missing or extra limbs, missing eyes, heads or ribs, or deformed skulls; in comparison, only three abnormal births had been registered in the five years prior. It's also been established that birds living in areas with high levels of radiation have statistically significant smaller brains and in general an increased rate of physical abnormalities compared to birds from uncontaminated areas. Invertebrate population (including bumble-bees, butterflies, grasshoppers, dragonflies and spiders) has significantly decreased, because they lay eggs in the top layer of the soil and that's where most of the radiation around Chernobyl is located. As to humans - the species that actually came up with nuclear power - it's stipulated that there has been a slight increase in birth defects in babies conceived within a few years after the explosion or in the number of miscarriages or premature deliveries among women of the affected zones, but again the numbers are most probably far beneath the levels claimed by the sensationalist sources.

Life goes on:

An example of how in a human-being heart can prevail over safety and reason is how some people would go back to the evacuated Chernobyl area villages, even though the radiation level is still too high for it to be safe. There's this letter you can see in the Chernobyl museum from a World War II veteran, in which he explains that he went back to Chernobyl because it's his home, and he fought the whole war to defend that home, and therefore it was his right to live there, and that nobody had the right to make him leave it, and how all he needed there was some tiny shop with basic supplies... Together with some humans, wildlife seems to be keen on inhabiting the vast deserted space - lately there has been an increase in the number of wildlife species found in Chernobyl which now include an elk, a boar, wild horses and many more. And incredibly enough, even inside the exploded reactor itself - the most inhospitable environment we could imagine for an organism - a certain type of black fungus called Cryptococcus neoformans and Cladosporium seems to be thriving on the highly radioactive walls, using its high amount of melanin to process the energy of ionizing radiation.

For the people who used to live there Chernobyl area became a kind of weird time capsule: things were abandoned in the hurried evacuation (which according to the government would last at most three months) but can still be found should their owners come back. Our guide in the museum told us a story which she heard from a visitor about how many years later he went back to visit his hometown Pripyat' and in the kindergarten which he used to go to, in the kids' wardrobe found his shelf and on that shelf - a pair of his tiny slippers.

Letters from people who were evacuated after the explosion explaining that they want to return to their homes, Chernobyl museum in Kiev:

Conclusions:

When scientists first started to exploit the power of nuclear reactions, they were saying that in a fragile area like this disasters could happen, but were estimating chances of it to lie at about 1 in 100000 years - in just a few decades we managed to produce a much longer list, with Chernobyl and Fukushima at the top of it. (Here's another list). Unlike Fukushima, Chernobyl disaster was a man-made one. But contrary to what many people are inclined to believe, human error during operation was not the main cause of the terrible accident. After many studies and disputes, the main causes of the explosion are believed to be the essential flaws in the reactor design, and while human factor definitely contributed to the conditions that led to the disaster (like operating the reactor at a power level of less than the required minimum of 700 MW), when you think about it, how can something so essential as the safety of a nuclear power plant be left down to flawless actions of operators? Or, for Fukushima, how can a nuclear plant with 54 reactors be built in an area that can be hit by tsunami? There is a lot of discussion about nuclear energy going on now and about how unsafe it seems to be in spite of opposite claims and how unprofitable it's growing in comparison to the other renewable sources - yet I heard that the Belarusian government has announced a planned construction of a new nuclear plant...

Looking at the chronology of the Chernobyl disaster, I get an overwhelming feeling of "prepared inevitability" - as in any major system change, there were the real causes (reactor design flaws) and the triggers (the unfortunate power outage in another regional plant and some mysteriously inexplicable actions by reactor operators). The thing is, triggers are always just a superficial contribution to any major accident (although it's this tip of the iceberg that people often swallow as the main reason - especially due to the coverage in media). But according to Hegel's dialectical theory - my favourite basis of systems analysis - it's the real causes that prepare any major event, which in my opinion in the case of Chernobyl and any other nuclear disaster to date is the fact that human race is simply not ready to exploit nuclear energy in a safe way. I have a feeling that scientists accidentally stumbled upon it and delighted by its novelty and seeming simplicity did what men always do with a new toy - started to play with it. Later on they came up with all sorts of rationalizations and logical arguments to justify the fact that it seemed like an incredibly advanced thing to play work with. And as always, decisions about its exploitation were confined to a tiny bunch of humans, who never turn out to be the wisest ones, but rather the most ambitious ones.

Personally, I think the nuclear disasters, along with any other human disasters, originate from the fact that the most important decision-making always rests with just a few - and inevitably flawed - humans. We choose governments based on who promises most - not on the levels of wisdom (or at least IQ). And then they start making decisions that are populistic rather than beneficial in long term. And when a disaster like Chernobyl strikes they will always try to sell us an idea that a scapegoat (like a young operator) was to blame for it. I think that for us not to have to deal with the horrible consequences of such flawed decision-making, we need to rethink our governmental systems. We elect/get stuck with governments based simply on their claims as to what they can do! Even some companies have special tests to check the abilities of job candidates - yet the people we elect to manage a country don't have to pass any of such tests, so we have no idea whether they know at least the basics of economics and management, or possess any common sense, wisdom and honesty. I believe that we'd get better governments if we elected teams of wise, honest, visionary, progressive people with thorough educational background and proper mindset (meaning a mental focus on efficient digitalized processes, governmental accountability, ecological awareness etc.) and use online surveys/voting as a performance check mechanism. So the elections wouldn't rotate around a political party, a certain charismatic personality that "sells" etc. - instead we'd have a list of roles for the team we need to elect and review the profiles and test scores submitted by various professionals who think they fit the roles. Actually, the whole governmental system should be based on the same management principles as a private company - citizens should be treated as precious customers, spending minimized, election process should be like hiring etc... And as a general conclusion, personally I think that wisdom and kindness (not ambition and sweet talking) combined with sound logic and systems thinking (not aggressive PR and populism) could provide a much better base for safe progress of the human race - a progress without nuclear disasters, man-made economic crises and sponsored wars...