Belarus - Easter buns and bureaucrats

Brief introduction into the history of Belarus:

"Where are you from?" - "I am from Belarus". - "Where? Belgium? Brazil?" These are the most typical comments I get from people when I tell them where I am from. They tend to think I pronounced it wrong and keep trying to give me suggestions of all the countries they know that start with a "b". I surrender and say "Byelorussia" instead of "Belarus". This always results in the inevitable "Ahh, Russia". Only a few people so far have surprised me with having heard of or even been to Belarus, a country which is not an administrative part or even autonomous region of Russia, but an independent state. Actually, it's not even the political side which matters, it's the fact that Belarusians have a national psyche and typical physical appearance different from Russians. Without a doubt there are many cultural similarities, similar cuisine and same festivals between many of the former USSR republics (especially Russia, Belarus and Ukraine), but it doesn't cancel the fact that those always exist in the bordering countries, yet it's the differences not the similarities that define the distinct ethnic groups.

Belarus has a different ethnic group from Russia and is nowadays a politically independent state (you could even say, too independent, as the country is in a kind of political and economic isolation from most of the world). Historically, it used to be part of the Kievan Rus (a network of principalities with major centers in Novgorod, Polatsk and Kiev) from 9th to 12th centuries. Then, between 13th and 15th centuries, it became part of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania - a powerful ancient European state where due to the predominance of Eastern Slavs the Ruthenian language was used for most state needs and where during the state reorganization the differentiation evolved between Russian, Belarusian and Ukranian languages. In the 16th century contemporary Belarus became part of the Lithuanian-Polish Commonwealth (Rech Pospolitaya) where the Belarusian aristocrats were gradually polonized (so became Catholic instead of Russian Orthodox). Between 16th and 18th century the Commonwealth was in a state of semi-permanent warfare due to continuous invasions by the Tatars.

Then following the mid-17th century's violent wars between the Commonwealth and the Tsardom of Russia, Sweden, Bradenburg and Transylvania and internal conflicts, the Tsardom of Russia annexed most of the Eastern part of the Commonwealth (including Belarus). In the end of the 18th century after an infamous division of Poland between its neighbours Russia, Prussia and Austria modern-day Belarus became a part of the Russian Empire, in which the Belarusian culture suffered from the first waves of Russification. Ironically, World War I was the short period during which the Belarusian culture started to flourish - the short-lived Belarusian National Republic was pronounced in March 1918 but ceased its existence at the age of a new-born (9 months) in January 1919 when it was pronounced the Belorussian Soviet Socialist Republic after the occupation of Minsk by the Soviet troops. Following the short Polish-Russian war, Belarus got divided between Poland and Russia in 1920, with subsequent Polonization policies in the Polish part and - after only a brief period of Belarusian revival - Russification in the Soviet part (a policy which resulted in the execution of the major part of the Belarusian elite).

In 1939 when Russia invaded Poland in the course of World War II, most of eastern Poland (including Belarus) was annexed by the Soviet Union. Following the German occupation during the World War II the nazis attempted to establish a puppet Belarusian government (Belarusian Central Rada) but in reality imposed a brutal regime, killing hundreds of thousands of civilians. During the war the Belarusian guerrillas (partisans) who were hiding in forests and swamps (using the unique local knowledge of these challenging nature zones) organized into a well-coordinated Resistance movement and were inflicting heavy damage on the German supply and communication lines, destroying the German trains, fuel dumps, telegraph wires etc. In total Belarus lost a quarter of its population during the war, including practically all its intellectual elite. In 1945 after the end of the war Belarus became one of the founding countries of the UN, followed by the Soviet Union itself.

The post-war period saw the shaping of the new Belarusian economy which was controlled exclusively from Moscow. During this period Belarus became a major industrial center of the Soviet Union, with a focus on heavy machinery. A lot of Russians migrated into Belarus during this time, which resulted in the decrease of the Belarusian peasant part - the "carrier" of the Belarusian language and culture. The "culture campaigns" enforced all throughout the Soviet republics at that time were meant to establish Russian as the language of the huge USSR and bring about a new amorphous uniform culture and on paper everybody's equality. Everybody's, but as it turned out in practice, except for the party officials. ("All animals are equal but some are more equal than others." George Orwell) As part of these campaigns, Russian was forced as the only language for teaching, work, public affairs and official documents. Probably due to the proximity to and the consequent ease of migration from Russia, after a hundred years of this cultural and linguistic genocide the Belarusian language fell into a coma, from which it never recovered.

After Belarus declared its national sovereignty in July 1990 and became part of the Commonwealth of Independent States as the Republic of Belarus after the break-up of the Soviet Union in 1991, there have been several attempts to revive the language as the primary native language for Belarusian people. These campaigns focused mainly on schools: all textbooks (except the natural sciences) were translated into Belarusian and for a few years kids (including me) were studying most of the subjects in Belarusian. Additionally, a much bigger accent was put on studying the Belarusian history, literature and the language itself. This was called "Belorussizatsiya", or "Byelorussification". They say, it did seem to be effective to a certain degree, as apparently small kids were starting to speak Belarusian to their parents at home. The parents were not happy... So Byelorussification failed, for probably the same reason that the language almost died in the first place - the main quality of the Belarusian psyche, tolerance, or rather over-tolerance. Now, tolerance is a beautiful trait in itself, but not when it's applied to the nation's political and economic situation and in an extremely high degree. In short, Belarusians are too tolerant, many times to the excessive degree of inertia, which means that they'd complain but never do anything about a situation that bothers them. I think it comes from the fact that the nation had to co-exist with so many nations through the years of history, but also due to the fact that for a hundred years people were brought up according to the Soviet principle of collective ownership which undermined any "taking initiative" gene that could have ever existed in the Belarusian people.

Modern-day Belarus:

These days Belarus is a dictatorship and while most people abroad are brainwashed by the media to believe that the dictatorship rests upon the falsified election campaigns, I'd say this dictatorship simply carefully designed and nurtured its electorate: middle-aged and elderly people who have never lived in a market economy and are afraid of it; numerous police who keep multiplying year after year as more people - not the brightest in the country - choose for good salaries and state flats; and the few entrepreneurs who happily exploit their rare networking and/or bribing skills as a main competitive advantage in the under-saturated Belarusian market.

As to these new Belarusian entrepreneurs, the country's weird combination of being a dictatorship and a market economy on a daily basis means that most of their energy is spent on trying to figure out a way to still make profit in a country where presidential decrees have one main target: to pump out of people as much money as possible to support the regime. Like I said, creating a network is the only competitive advantage the local entrepreneurs ever need to gain: once they figure out how to co-exist with the regime, they are pretty much safe from then on, as the market, starved for consumer goods and services during the Soviet era of asceticism, is far from being saturated in any of its industries and niches. The thing is, it takes a certain type of character to be able to run a business or simply live in a lawless state where the government has all the power and the individual - none. This means that many young people who don't have that type of character just try to leave the country.

I also left, but not before I tried to fit in, and co-exist and even run a business (I started a books translations publishing business for a media holding). And then it gradually dawned on me that there's no point in trying to fit in in a system which is actually carefully designed to leave you out. There are just too many elderly people in an aging nation who at the end of the day are happy with their miserable but secure pensions and would never put it at risk by trying to vote differently in any election. Naturally, the Belarusian government doesn't stop all the young people who leave Belarus every year - I think, this government knows that once the restless ones leave, it's actually left with a more stable, manageable electorate.

Our stay in Belarus:

Quite in line with the above introduction on what the modern state of Belarus is about, most of our visit to this country was somehow filled in with all sorts of nuisance activities. On crossing the border we already had our first show of inhuman bureaucracy, as an old lady who was going to visit her Belarusian daughter was sent back to Lithuania because she had a missing page in her Lithuanian passport (the Lithuanian immigration officers had no problem with it). In Belarus from day one it was a never-ending paperwork hustle. On the first day we applied for my passport and registered Jordi as a temporarily residing foreigner (it cost us half a day). Then we needed to go get an invitation for his mum to be able to come visit my family while we were in Belarus during her Easter holiday (another day and some "new presidential decree" surprises). Then we needed to go all the way to the Minsk airport to drop off the original invitation in the postbox of the consular office. Then Jordi's mum came and spent half a day at the consular office getting her visa on arrival (after they made her buy a Belarusian insurance). And then we needed to register her as a temporarily residing foreigner (another half day, but by this time to keep up with the never-ending high inflation the usual indexation of public fees took place so we had to pay more and go to the bank twice).

Then we all went to Kiev for a few days and Jordi's mum left for Spain, but Jordi came back so there was the usual Belarusian border crossing (with the inevitable purchase of a Belarusian insurance). And then we had to go register him again as a temporarily residing foreigner (this time it was really "temporarily" - for just about 4 days, but still had to be applied and paid for). And then we had to go a few times just to check if my passport was ready. And of course totally in line with the usual inefficient way things are done in Belarus, the ladies who process the application kept telling me that it had been two weeks that they hadn't gone to pick up the passports in the regional capital. And of course perfectly in line with the way things are done, I got my passport only on the last working day before the weekend we had to leave for Brazil.

To sum up, any tiny public affair that has to be arranged in Belarus is an ordeal; any public office you'd visit is behind closed doors and everybody has to knock in the hope that the officials inside will let them in; and anything you need to arrange will be difficult and expensive and regulated by some fresh presidential decree (in this respect the regime is very productive). Jordi was so frustrated by all these visits that he even claimed that in Belarus even I become very inefficient... Well, I think this is naivety of a person who never co-existed with a Soviet or a dictatorship system :-).

Among all these visits to the public offices we did have a bit of time to do other things: spend time with my mother and sister, visit my godmother, grandmother, my aunt; find a cat for my mum (check out Maksik in the photos below); go to the forest a few times and even do some sawing exercise (of course, not on a living tree :-) in the hope to make a scratching device for ungrateful Maksik who never even touched it; visit Minsk; visit Kiev; sample all the Belarusian foods; celebrate Easter the Belarusian style by making Easter buns, painting Easter eggs and going to church to get all this food sprinkled with holy water. Actually, it's quite lucky that our last couple of days in Belarus coincided with Easter, as Jordi had a chance to learn the Easter buns recipe from my mum (otherwise it would die with her :-) and be surprised at how religious the modern Belarusians are. (It's indeed a curious trend - like some kind of religious dam broke after the collapse of the Soviet Union and the lifting of the prohibition to practice any religion.)

Every time I come to Belarus, I see contradicting things: most people seem to be struggling even harder to keep up with the never-ending high inflation, but some people can buy apartments in the new fancy blocks of flats. And the President keeps building new "toys" (a skating ring, a ski resort, a dolphinarium). Most people have just enough money to buy basic food, but some people dine out in fancy restaurants that open in the country and regional capitals every year. Marginalization is a normal phase for any transition society, but in Belarus it got its own unique flavour due to the fact that transition towards market economy is hosted by a dictatorship. I'd say people in the Belarusian society live in parallel universes: the few entrepreneurs prosper, build luxurious villas and go on expensive vacations; some young people have decent jobs but can only afford a bit more and a bit fancier stuff than the parents; the pensioners are happy they have enough money to buy bread; and the middle-aged parents of the young generation seem to be lost as to whether to quietly join the pensioners in a short while or try to catch the wave of the market economy.

Jordi says his highlights for Belarus are the forest (it's endless and everywhere) and the street cats (very beautiful and cuddly). I am of course very biased towards my country, but I do think that in Belarus we have awesome forest with lots of berries and mushrooms, gorgeous lakes and rivers that make great picnicking spots in summer, nice spots to do nordic skiing in winter, cool DJ's and great discos that are much more fun than anywhere else in the world. We also have "smetana" - super tasty sour cream which is the base of the local cuisine, and beautiful chestnut blossom in May. Surprising as it might sound, Belarus does have a baby-size tourist industry, but it's targeted exclusively at Russians (they come in summer to stay in sanatoriums or rented bungalows in the middle of the forest on the banks of rivers or lakes). I'd say if anyone would consider a tourist visit to Belarus, they should definitely come in summer. That's when the country is at its best - it's sunny, the forests are full of berries and the water in the rivers and lakes is warm, so you can have barbeque with the locals, swim and camp. It's too bad that the two times that Jordi visited Belarus were both in winter, but we will correct that some time in the future.

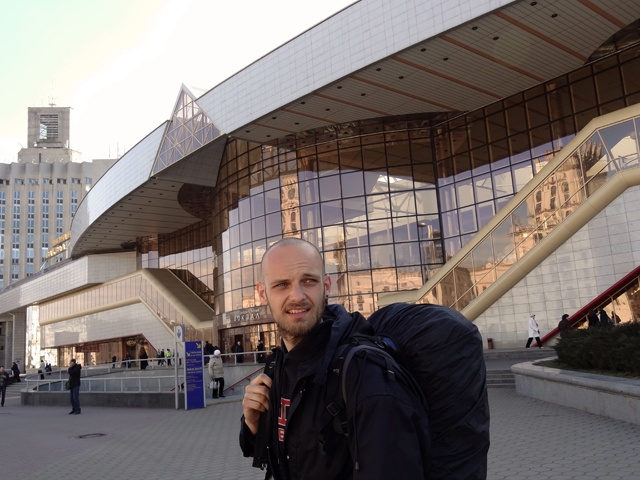

Minsk, train station:

Osipovichi, birch tree alley:

Osipovichi, two of the several churches that were built over the last few years for the increasingly growing parish:

One of the truly amazing things during our visit to Belarus was the weather - on any given day dazzling sunshine and heavy snowfall would replace each other in a matter of minutes, many times a day. This is not how spring used to be in Belarus, but we keep hearing similar things about the local weather all around the world. One word for it - global climate changes. Below are photos from a snowfall period:

Osipovichi, being a tiny provincial town, due to its location on the crossroads of many railways is an important train station (hence the monument of an old train). It's a two hours drive by "elektrichka" - electrical train - to the capital, Minsk:

A typical neighbourhood in a typical Belarusian city:

The forest in Belarus is just everywhere, for instance it's 5 minutes walk from my mum's place, and almost anybody else's place :-) Almost all of this forest is natural, with only 22% planted:

One day we decided to make my mum's cat a fancy scratching device - it took us about half an hour to saw off that piece with our miserable saw :-):

More views of Osipovichi:

During Jordi's mum stay in Osipovichi (she is a teacher) we visited a school and got some Easter cards from kids in the crafts lesson :-):

Some (cloudy) views of Minsk:

This is the location of the cheapest "buffet-like" self-service restaurant in Minsk, Nemiga area:

GUM, or "State Universal Shop" - a huge multi-storey shopping legacy of Soviet Union, which can still be found in any Belarusian regional capital:

Night views of Minsk:

Easter celebration:

Some family photos from our visit: